Last updated: July 15, 2025

Applying for an ERC grant is intellectually demanding, whether you’re an early-career researcher or an established scientist. You may have written grants before. Maybe a lot of them. You know how to frame objectives, align with a call for proposals, and demonstrate impact. And even if you haven’t, you’ve likely encountered well-crafted proposals and learned what “works” in other funding contexts.

With this article, we hope to encourage a shift in perspective: the ERC operates differently, and that difference demands a different, deeper kind of thinking.

At its core, the ERC holds a single, deceptively simple criterion: scientific excellence. But here, excellence means more than just doing good science. It is about originality, ambition, and depth: identifying a genuine gap in knowledge, proposing a bold, non-incremental idea, and building a project that is both visionary and feasible. It’s not just about advancing your field – it’s about disruptively shifting the conversation within it.

To meet this high standard, your thinking must stretch beyond what typical national or applied grants expect. Crucially, this is not abstract or generalized thinking. It must be deeply grounded in your own scientific field – its questions, tensions, assumptions, and possibilities. ERC thinking requires that you position your project within your discipline while also challenging its boundaries.

To make matters more challenging, the ERC provides no detailed template or checklist. That freedom is intentional, but it makes the task even harder. Without a predefined structure, you must lead the conceptualization and shape how the idea coheres.

Often, it’s the failure to recognize these demands that causes proposals to falter.

Not necessarily because the science is weak, or the researcher lacks talent, but because the deep-thinking process did not precede and iteratively impact the writing process. Instead, applicants often substitute that kind of rigorous, field-anchored reflection with familiar grant-writing habits: following a formula, rushing into writing, or relying on instincts like cautious framing, recycled concepts, incremental steps, declaring that critical conceptual aspects are “to be developed later”, etc.

Importantly, ERC proposals are reviewed by top-tier scientists. They expect clarity without oversimplification, ambition grounded in preliminary findings, and a project shaped by genuine scientific insight. Vague or underdeveloped intellectual foundations rarely hold up under scrutiny. The groundwork must already be there.

This article is designed to help you build that foundation, not through writing tips, but through the thinking process that makes a strong ERC proposal possible.

If you consider applying, this is where your work begins.

Step-by-Step Thinking: Building a Competitive ERC Concept

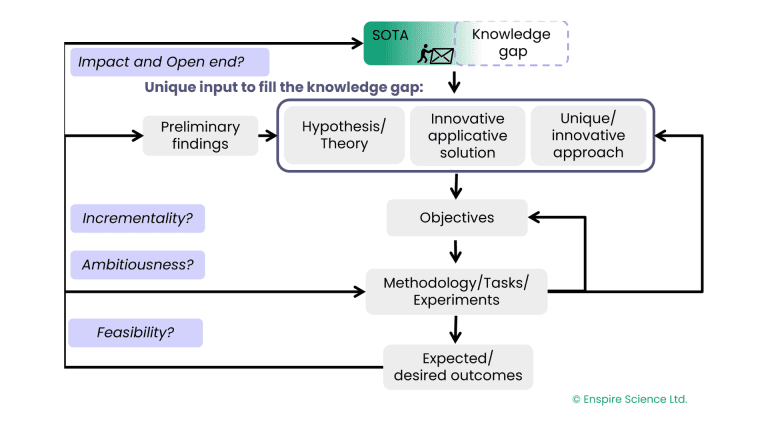

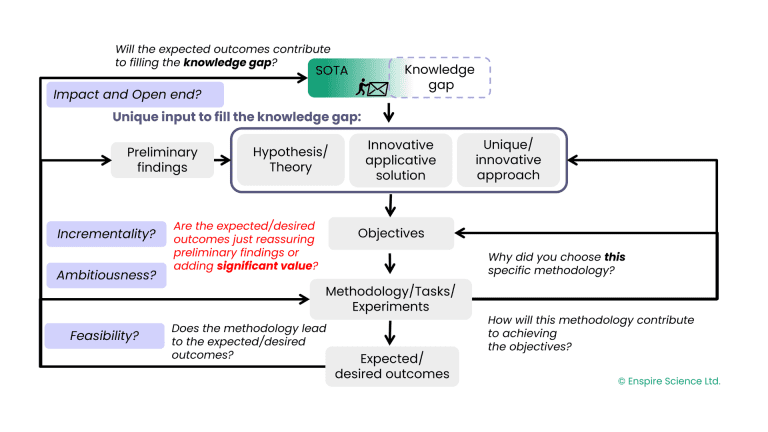

A competitive ERC project begins with a deep understanding of your field and a clear view of where that field falls short. The first step in the thinking process is thus identifying the knowledge gap you wish to tackle. The knowledge gap you identify must represent a significant, unresolved issue in the current state of the art. As outlined earlier, ERC proposals are not about validating what we already know or extending familiar lines of inquiry. Reviewers expect you to surface questions that have conceptual and substantial weight and that hold the potential to transform understanding in the field.

Once that gap is articulated, the real challenge begins: consolidating a research idea to address it. This is where many proposals falter. As we noted earlier, failure often stems not from a lack of scientific quality but from insufficient early thinking. It’s not enough to state that a problem exists – you must show how you will approach it, and why your way of thinking reflects genuine insight, originality, and intellectual risk.

The idea can take different forms, e.g.:

- A bold hypothesis or theoretical framework (as expected by many panels)

- A creative solution to a persistent challenge

- A new conceptual or methodological approach

What matters is that the idea reflects the unique ERC expectations: it must be ambitious and high-risk, non-incremental, and firmly grounded in your scientific context and preliminary work. That grounding is critical. ERC does not reward abstraction- it rewards deep, thoughtful engagement with your discipline’s tensions, assumptions, and blind spots, as well as the ambition to challenge them.

At this stage, you should ask yourself:

- Is the concept intellectually complex?

- Does it involve unconventional or cross-disciplinary thinking?

- Are there real analytical or theoretical challenges at stake?

- Is there a high level of scientific uncertainty that raises the project’s risk and its potential reward?

As we emphasized earlier, ERC reviewers expect clarity, but also depth. Promising to define your theoretical framework or approach “later” is unlikely to meet that bar. The intellectual coherence must be visible from the outset, and it must emerge from your own thinking, not from a similar past effort, template or checklist.

From here, the idea should give rise naturally to your project’s objectives: the concrete steps needed to explore the concept or test the hypothesis. The methodology should follow logically, presenting a clear and justified plan of action for achieving each objective.

As you develop this part, make sure to answer the following key questions:

- Are the tasks/experiments aligned with the proposed objectives?

- Is this the most effective and appropriate methodology for the problem?

- Is it clear how each step contributes to testing the hypothesis or answering the core questions?

These, in turn, should lead to a reflection on your project’s expected outcomes. ERC doesn’t demand certainty, but it does demand scientific value that arises from a solid research project. Whether or not your hypothesis holds, your outcomes should extend the field’s knowledge and possibilities: introducing novel significant findings, challenging assumptions, opening new research directions, or introducing new conceptual frameworks.

Ask yourself:

- Am I able to credibly anticipate possible outcomes? This should demonstrate expertise in the chosen methodology and adequate planning of the experiments.

- If the hypothesis is wrong, do the results still offer insight or direction? Will the results contribute to filling the knowledge gap?

- Will the expected outcomes just reassure preliminary findings or add significant value to the scientific community?

- Will the outcomes help fill the knowledge gap? Generate new lines of inquiry or shift the conversation in your field?

Throughout the process, keep in mind the importance of the flow of thought and coherence. A strong ERC proposal is not a collection of parts – it needs to have a conceptual structure. The knowledge gap, the idea, the objectives, the work plan, and the anticipated outcomes must build on one another with clear internal logic. Starting midway, or skipping steps in the thinking process, may lead to a lack of a unifying conceptual thread, in turn compromising the project’s scientific reasoning, ambitiousness, and novelty, which are key to ensure a competitive ERC proposal.

Conclusion

Crafting an ERC proposal is not a linear task, it’s an iterative process of concept development, reflection, and writing. As we’ve emphasized, ERC doesn’t just ask for a well-written plan. It asks for a project that is conceptually whole, intellectually bold, and deeply grounded in your scientific context.

That kind of project takes time to build. It must grow from your understanding of where something essential is missing and your vision for how it might be reimagined. We encourage you to take that time. Think carefully through each element. Explore the connections. And allow your project to reflect not just your expertise, but your voice as a scientist – your ability to see differently, and to propose something new.

If you’re ready to begin writing, see our companion articles on “logical jumps” and “feeding the reviewer”, which focus on turning strong ideas into compelling, readable proposals.