Applying to the ERC and want to gain dedicated tools for success?

Risk is probably the most important aspect of ERC. Unfortunately, it also happens to be the most elusive one. Many researchers often wonder what high-risk research means and how to express it in their application. Consequently, they struggle to assess whether their project entails the level and type of risk expected by the ERC.

The observant among you probably noticed that the term “high-risk” no longer appears in the official ERC documentation (starting 2024), and may have mistakenly thought it was no longer relevant. However, we must reassure you – the expectation for high risk in ERC remains despite the terminological changes. To quote ERC representatives: “Frontier research somehow by definition (means) taking risks. So, the risk element is embedded and it continues to be so.”

The terms “high-risk” and “high-gain” have been replaced with “ambition” and “ground-breaking nature”. These changes were made to simplify evaluation and overcome confusion associated with the previous terms. Nevertheless, the essence of the grant remains unchanged. ERC, as always, seeks ambitious frontier research that significantly pushes boundaries.

In this article, we will decipher the ERC high-risk – ambition enigma and offer clarifications that will assist in the process. The following guidelines and recommendations are relevant to all scientific disciplines and to researchers from all ERC grant categories.

The PI’s role in establishing the ERC High-risk

First – an important note before thoroughly analyzing the high-risk in ERC. Since ERC is an investigator-driven grant – it is important to focus on the PI’s (Principal Investigator) role in ensuring this aspect. Therefore, when assessing the high risk nature of the project, next to the novel concept of the project, we have to look at what the PI brings to the table.

The PI needs to be both creative and with the relevant intellectual capacity to propose original, non-trivial, and groundbreaking ideas – all inherent components of frontier research. These will manifest in the high-risk aspect. In this article we will refer to these PI attributes as the “driving forces” required for presenting a highly competitive proposal to the ERC. Needless to say, reviewers will be expecting and closely assessing this during the evaluation process.

Having understood the PI’s important role in establishing ERC high-risk, let us continue to properly understand this aspect to its core.

The two dimensions of high-risk in ERC

Without clear guidelines to work by, the concept of ERC high-risk or ambition can be a very complex and difficult one to decipher. A preliminary step to deconstructing and clarifying this concept is dividing it into two important dimensions. The first dimension refers to the type of risk that the project entails. Here we make a distinction between “Operational risk” and “Conceptual risk”. The second dimension addresses the feasibility of the proposed scientific approach.

Type of Risk: Operational vs. Conceptual

Operational and conceptual risks are inherently different. It is important to understand this difference in the context of ERC. When referring to operational risk, the focus is usually on risk that can be diminished by acquiring resources (time, materials, personnel, equipment, etc.). In other words – operational risks can typically be solved given the right budget.

On the other hand, Conceptual risk relates to scientific challenges that require more than acquisition of resources. Such scientific challenges, by definition, are prone to (scientific) failure. The conceptual high risk of the project is expected to stem from – and be supported by – the PI’s creativity and leadership in the scientific domain, as we have established above. Needless to say that in ERC the Conceptual high risk is the favourable one.

An effective method that can help determine the level of conceptual risk that a project carries involves two parts:

- Assessing the level of uncertainty involved in the research, and

- Assessing the extent and amount of assumptions required in order to plan the research.

Research that warrants many far-reaching assumptions typically carries a high conceptual risk. In other words, if the answer to your research question or hypothesis is somewhat clear, or there exist good estimations about the project outcome, the conceptual risk is low.

Having a high level of scientific uncertainty in research is a practice that many find to be unorthodox. It contradicts the typical incremental and stepwise progress which aims to reduce, eliminate and/or avoid uncertainties along the research path. In fact, experience shows that the ERC high-risk requirement is perceived as counterintuitive for many researchers. This is generally because it expects the PI to step out of the comfort zone and propose bold, novel, non-incremental ideas (we’d recommend reading more about the “non-incremental challenge in ERC” ). These ideas hold the promise of significant and important scientific breakthroughs.

High-risk and hypothesis-driven research in ERC

In some cases, the issue of high risk and level of uncertainty is, and should be, manifested by the concept of hypothesis-driven research. In this sense, high-risk and hypothesis are tightly connected. This is because proposing an ambitious, new and significantly uncertain scientific hypothesis, based on initial and promising preliminary results, usually carries the expected conceptual high-risk in ERC. Discovering whether the initial hypothesis is true or false only after the research is done, usually indicates that the project is indeed high-risk in nature.

What about operational risk in ERC?

In contrast to the Conceptual risk discussed above – if the risk presented in an ERC proposal is merely Operational, it is very unlikely that the project will be deemed competitive enough. In most cases, ERC will not fund projects that present only operational risks that seek large-scale funding to resolve them.

One typical “family” of research structures, which we’ve labelled “fishing expedition research” , fall under this definition. Hence, they tend to fail in ERC. Since this “family” is fairly large, we put it in the spotlight. However, the case of operational risk in ERC spans beyond “fishing expeditions” and there are many other research structures that will fail due to lack of conceptual risk.

Having established that conceptual risk is favored over operational risks in ERC, let us venture to the second dimension at hand.

Feasibility of the scientific approach

The feasibility of the scientific approach is the second dimension to take into account in the context of high-risk and ambition in ERC. When viewed in general cases, risk and feasibility can seem to contradict each other. High feasibility is perceived to diminish the risk. Vice versa – a high risk project implies that its feasibility should be low (or in question). In ERC however, these do not necessarily contradict. In fact, both conceptual high-risk and feasibility are required. This can be seen from the dedicated question on this matter which ERC reviewers need to answer: “To what extent is the outlined scientific approach feasible bearing in mind the ground‐breaking nature and ambition of the proposed research?”

Simply put – at the conceptual level, the project needs to aim high, be bold and ambitious. But the plan on how to get there, which the PI puts forward, needs to seem feasible enough to the reviewers. To show the feasibility of the scientific approach convincingly, projects should include a detailed and realistic methodological plan, designed and tailored to explore the new conceptual theory or model proposed. The feasibility is also expected to rely on preliminary findings that support the novel idea and/or approach of the project. Finally, the PI needs to show the capacity to execute the plan put forward, which should be evident from the PI’s track record. In that sense, the feasibility of the scientific approach corresponds with the notion that the PI is best positioned to carry out this project and has the right “driving forces”.

When highlighting the feasibility through the PI and his/her capabilities, it does not hurt the high-risk. Rather – it is this feasibility which helps to achieve the novel and high-risk target.

The right high risk for your ERC project

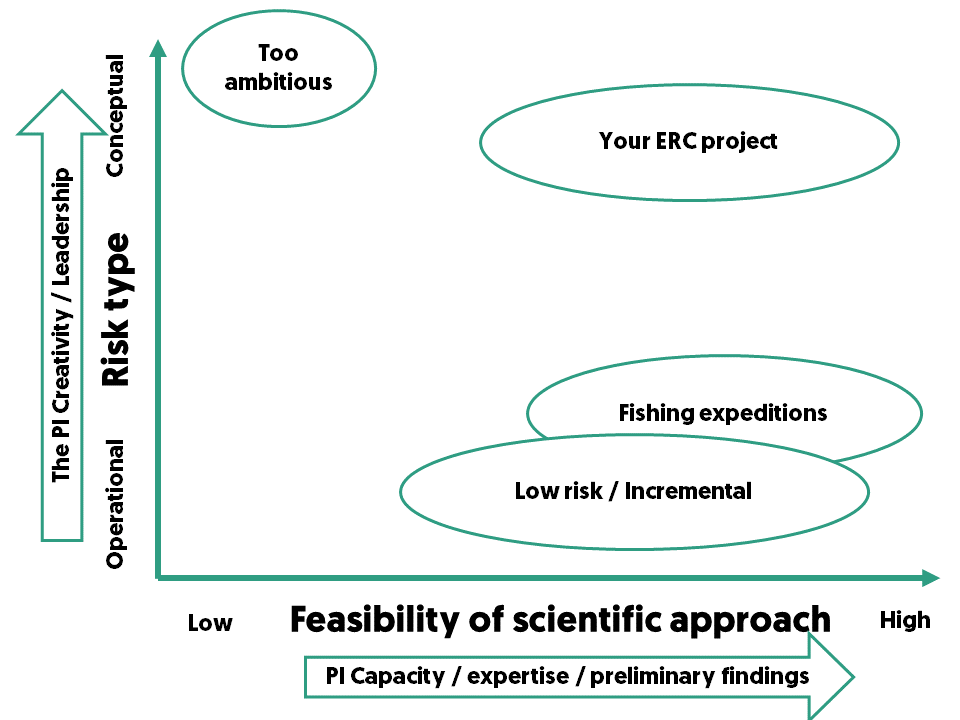

In the following diagram, the x and y axes represent the two dimensions discussed – feasibility of the scientific approach and the type of risk, respectively. In both dimensions the PI’s profile is paramount for establishing the right type of risk on one hand, and the level of feasibility of the scientific approach on the other. The arrows accompanying the axes represent the driving forces essential for directing the nature of the project to be in line with the ERC high-risk expectations.

Below we discuss the positioning of projects along these axes, and describe how to find the right balance between them:

The upper left corner (conceptual risk and low feasibility), is the case of the “overly ambitious” research project. It is usually a type of “blue sky” research idea that has little to no proven feasibility (conceptually and methodologically). An example for this is a project which relies entirely on a very novel and ambitious method with no initial proof of concept to its feasibility. This case is not too common, but we have seen ERC applicants mistakenly assume this to be the type of “high-risk” that ERC is seeking. Needless to say, this is not a recommended practice. Indeed, such projects tend to be rejected.

In the bottom right area – the risk is operational and the feasibility is high /potentially high. Here, we typically see projects that carry low risk and may be perceived as incremental research projects. In this case, the project showcases incremental progress with respect to the state of the art (be it the PI’s work or not). While this promises its success, it lacks the expected conceptual leap forward. Projects that fall within this area may also present the “fishing expedition” research projects discussed above. Typically, such projects are not successful in ERC either.

Conceptual risk and satisfactory feasible approach

Our focus of interest is the top right corner of the chart. Here – the risk is conceptual and the feasibility of the approach is relatively high. Importantly, both dimensions need to correlate with the PI’s profile and contribution – creativity and leadership on one hand, and capacity, expertise, and supported by preliminary findings on the other. Experience shows that this is typically the best high-risk balance of a competitive ERC project proposal.

Conclusion

To sum it up – ERC is looking for risky and ambitious projects. These need to stem from the original thinking of an excellent researcher that is best positioned and has the ability to carry out the project through a structured scientific approach, expected to reach significant breakthroughs.

If you have any further questions about ERC high-risk, or any other ERC related matters – please contact us!